by Betsy Herbert

"Earth Matters," published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel 02/18/16

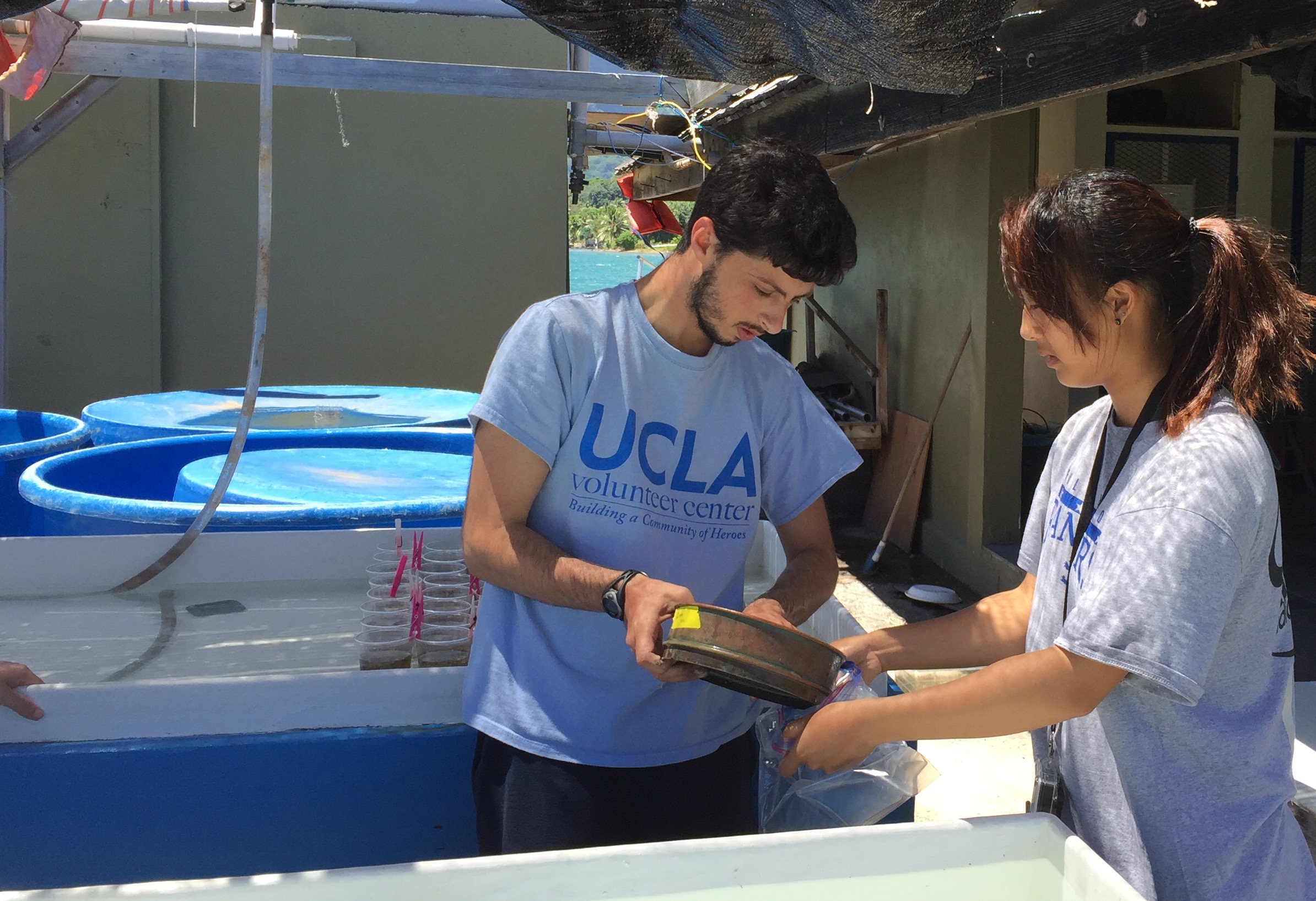

Undergraduate researchers from California work at the UC Berkeley Gump Research Station in Moorea, French Polynesia. Betsy Herbert — Contributed

In month nine of my yearlong trip around the world, I decided to hang out on the island of Moorea in French Polynesia during the offseason. What a great way to experience this tropical paradise and to appreciate the scientific research underway here!

I began my stay by going for a group swim in a crystalline turquoise lagoon alongside 4-foot sting rays and black-tipped reef sharks. While the sharks were not at all aggressive, the rays seemed downright affectionate, sliding against our bodies and peering at us from strangely human-looking eyes.

My beach bungalow at the laid-back Kaveka Hotel was an idyllic retreat with “Bali Hai” views of Cooks Bay and the coral reef that separates it from the Pacific Ocean. Directly across the bay, I could see UC Berkeley’s Gump Research Station, the hub of scientific inquiry that has helped to make Moorea the most studied island in the world.

In 1975, Richard B. Gump, the original owner of San Francisco’s premier gift store, donated the land on Moorea to UC Berkeley to establish the research center, with the goal of analyzing the island as a model ecosystem to understand how global changes are affecting it over time.

Frank Murphy, associate director of Gump Research Station, said Moorea makes an exceptional natural laboratory. The island is small enough (about twice the size of Manhattan) to enable scientists to construct an inventory of all of the non-microbial species known to be living there. The Moorea Biocode project was designed to accomplish this feat and is the first of its kind.

Envisioned by the center’s director, Neil Davies, Moorea Biocode enlisted researchers from 2008-2010 to ascend jagged peaks, slog through tropical forests and dive among coral reefs to sample the entire spectrum of Moorea’s animal and plant life. The end result will be a library of genetic markers and physical identifiers for every species of plant, animal and fungi on the island — and this library will be available to the public.

The coral reefs and lagoons that surround the island of Moorea have been of particular interest to “swarms of scientists who come here every year,” says Murphy, as part of the Moorea Coral Reef Long-term Ecological Research project. Though coral reefs are one of the most diverse ecosystems on earth, worldwide almost 20 percent have been lost and another 35 percent could be lost by 2050.

These scientists have been monitoring and recording data about Moorea’s coral reefs for more than 15 years.

“This approach has considerable potential in better understanding how global climate change will affect reef corals, and we are working toward developing modeling approaches to achieve this outcome,” according to Peter Edmunds, a researcher from Cal State Hayward.

Another exciting project envisioned by Davies is the making of a digital model of the entire Moorea ecosystem, including its biological, physical and human cultural aspects. Named “Moorea IDEA,” for Island Digital Ecosystem Avatar, the end product would be an online 3-D model. Scientists and others could pose questions online, and the model would simulate how different impacts might affect the entire ecosystem.

I asked Murphy if people on Moorea were worried about sea-level rise, as a result of global warming.

“We’re in better shape than lots of places,” he said. “If worse came to worse and everything crashed, we could almost be self-sufficient.”

That’s because Moorea has tall mountains and considerable arable land. Other places, such as in the Motu archipelago, Murphy posits, “will be underwater in 60 years, because the atolls don’t have any high ground. A whole history of culture will be going underwater.”

Betsy Herbert is a freelance writer on a year-long journey around the world. You can read her travel blog and environmental articles on her website, www.betsyherbert.com.