by Betsy Herbert

March 8, 2016

In month nine of my yearlong trip around the world, it was time for a break. I took a 5-hour flight from Auckland, New Zealand to Papeete, Tahiti and then took the ferry to the island of Moorea. After an hour long ferry ride, I hopped on a public bus in Moorea that took me directly to my hotel. The buses run with the ferry schedule, so it's really easy, and it cost me only $2.00.

My beach bungalow at the laid-back Kaveka Hotel was an idyllic retreat with “Bali Hai” views of Cooks Bay and the coral reef that separates it from the Pacific Ocean. Since I was here during the off season, things were quiet and there were very few other guests at the hotel.

The Kaveka Hotel on Cook's Bay in Moorea where I stayed in a bungalow for 10 days.

Wi-fi was the only way for me to get internet access in Tahiti. It cost $10.00 per day at the hotel and it was slow as all get-out. It didn't work at all in my bungalow, so every day I would sit in the lobby or restaurant with my computer and write for about 5 hours. In the evenings, I would typically enjoy jazz or Polynesian music at the hotel by local musicians.

The restaurant was built on stilts over the bay and I would look down through perfectly clear water at brightly colored tropical fish, as they waited for diners to throw them bread crumbs. I would also gaze at the gorgeous views across the bay.

View across Cook's Bay from the Kaveka Hotel.

Moorea is a quiet island, especially during the off-season. I didn't have a car. The hotel had a van that would make runs into town most mornings. Sometimes I would take the 45 minute walk if it wasn't too hot. But there were very few services offered in town other than stores selling local crafts, and Tahitian black pearls. These are cultured pearls, grown locally, and they are quite beautiful. I did my part to help the local economy!

When you're out and about on Moorea, there are huge flowering hibiscus trees and bushes everywhere.

HIbiscus flowers are always in bloom in Moorea, and I would often pluck one to wear in my hair, as is the custom here.

The staff at the Kaveka Hotel was very friendly and attentive. Tim, the hotel's primary host, was brimming with good nature. His mantra was "Tres, tres, bien!" followed by a big smile. I don't speak French, but the staff spoke some English, as well as some Spanish, so we were always able to communicate.

One evening as I was having dinner at the hotel restaurant, a tiny reptile jumped out of the vase of flowers on the table. I picked him up with edge of my napkin and placed him back in the flowers. I wondered what kind of a reptile he was. I called the waiter over to investigate. He identified him as a baby gecko. My first encounter with native wildlife!

My waiter at the Kaveka Hotel restaurant, with a baby gecko perched on his hand.

Close-up of the baby gecko, my first encounter with wildlife in Moorea, other than mosquitoes.

Every evening, just before sunset, a team of rowers would glide past my hotel. Rowing is a popular sport here.

Rowers on Cook's Bay gliding past the Kaveka Hotel just before sunset.

And sunsets were typically glorious. . .

Sunset on Cook's Bay at the Kaveka Hotel's restaurant/pier.

My second day in Moorea, I took a short cruise to a nearby crystalline turquoise lagoon, where a group of us would swim alongside 4-foot sting rays and black-tipped reef sharks. The cruise was hosted by local people.

One of the cruise staff on our way to view sharks and rays.

While the sharks were not at all aggressive, the rays seemed downright affectionate, sliding against our bodies and peering at us from strangely human-looking eyes.

Four-foot diameter sting rays lying some five feet below the surface of the water. They were very friendly!

Our guide and me after enjoying a wonderful time swimming with the sharks and rays.

Directly across the bay from my hotel, I could see UC Berkeley’s Gump Research Station, the hub of scientific inquiry that has helped to make Moorea the most studied island in the world.

Directly across Cook's Bay from my hotel, I could see U.C. Berekely's Gump Research Station.

I decided on a lark to pay a visit to the research station, hoping to interview one of the directors for a column called Earth Matters, which I write monthly for the Santa Cruz Sentinel. Since I had no cell phone reception, I hopped on one of the hotel's bicycles and pedaled around the bay to the station.

I was directed to the office of Frank Murphy, the research center's associate director. He was apparently in a meeting when I arrived, but he graciously stepped out to see me. He agreed to the interview, which we arranged for later over lunch at the Kaveka Hotel restaurant.

I did a some research on-line before the interview. In 1975, Richard B. Gump, the original owner of San Francisco’s premier gift store, donated the land on Moorea to UC Berkeley to establish the research center, with the goal of analyzing the island as a model ecosystem to understand how global changes are affecting it over time.

Later, during our interview, Murphy said that Moorea makes an exceptional natural laboratory. The island is small enough (about twice the size of Manhattan) to enable scientists to construct an inventory of all of the non-microbial species known to be living there. The Moorea Biocode project was designed to accomplish this feat and is the first of its kind.

Envisioned by the center’s director, Neil Davies, Moorea Biocode enlisted researchers from 2008-2010 to ascend jagged peaks, slog through tropical forests and dive among coral reefs to sample the entire spectrum of Moorea’s animal and plant life. The end result will be a library of genetic markers and physical identifiers for every species of plant, animal and fungi on the island — and this library will be available to the public.

The coral reefs and lagoons that surround the island of Moorea have been of particular interest to “swarms of scientists who come here every year,” according to Murphy, as part of the Moorea Coral Reef Long-term Ecological Research project. Though coral reefs are one of the most diverse ecosystems on earth, worldwide almost 20 percent have been lost and another 35 percent could be lost by 2050.

These scientists have been monitoring and recording data about Moorea’s coral reefs for more than 15 years and will help to increase understanding of how climate change will affect coral reefs.

Another exciting project envisioned by Davies is the making of a digital model of the entire Moorea ecosystem, including its biological, physical and human cultural aspects. Named “Moorea IDEA,” for Island Digital Ecosystem Avatar, the end product would be an online 3-D model. Scientists and others could pose questions online, and the model would simulate how different impacts might affect the entire ecosystem.

I asked Murphy if people on Moorea were worried about sea-level rise, as a result of global warming.

“We’re in better shape than lots of places,” he said. “If worse came to worse and everything crashed, we could almost be self-sufficient.”

That’s because Moorea has tall mountains and considerable arable land. Other places, such as in the Motu archipelago, Murphy posits, “will be underwater in 60 years, because the atolls don’t have any high ground. A whole history of culture will be going underwater.”

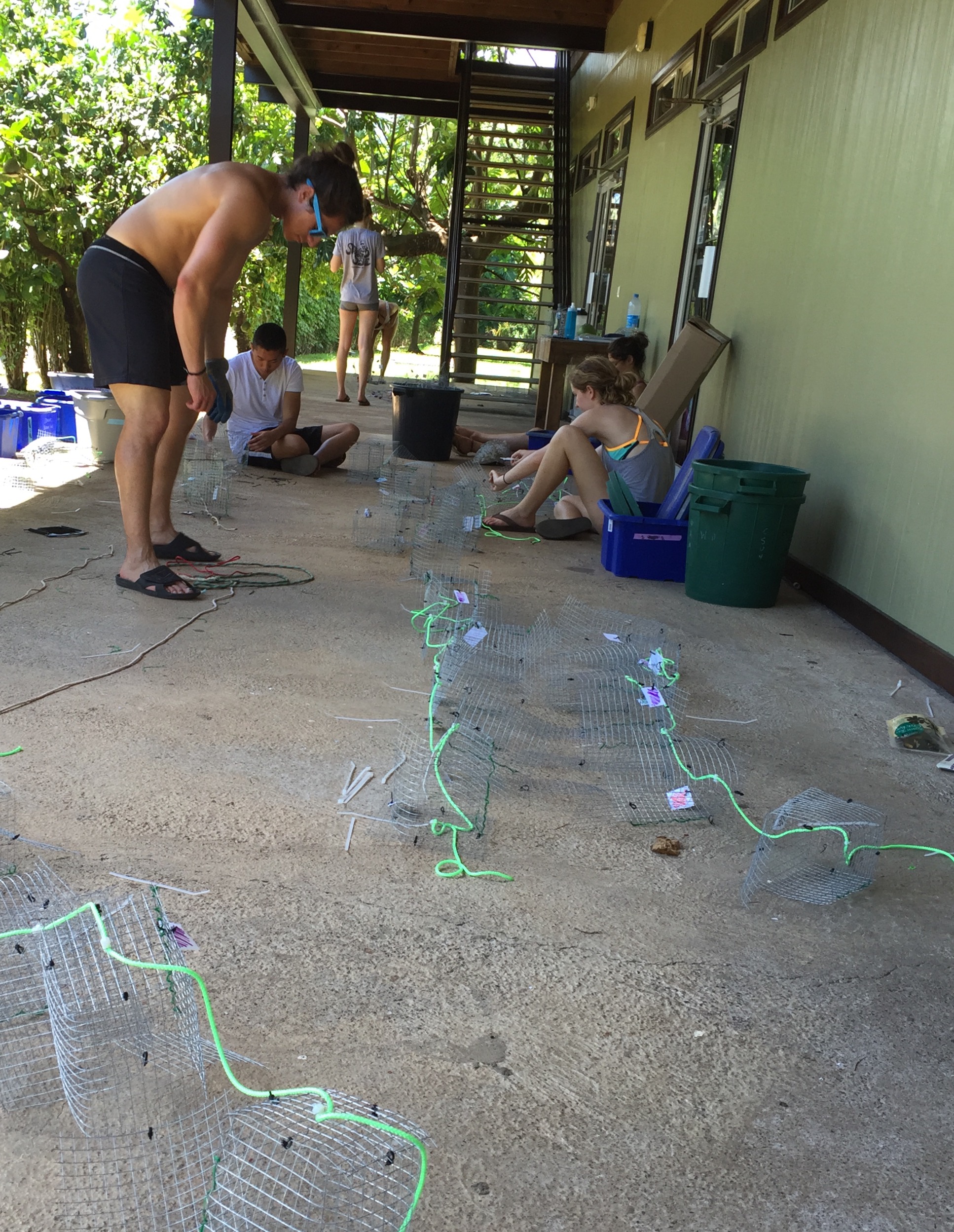

The Gump Research Station trains undergraduate researchers from all over the world. Below are a few photos that I took of these researchers on the job at the station:

After I left Moorea, I wrote and published my column. You can read it on this website under "News Articles."

After my interview with Murphy, I had to get ready to leave Moorea. I was headed next to Easter Island, five hours east from Tahiti by plane.